Why Nations Fail: Trapped in the Eternal Cycle of Power Games, the Colombian Case

Escaping the Trap of Mimetic Rivalry Through Innovation and Renewal

In an age where global tensions simmer—from U.S.-China tech rivalries to precision warfare reshaping the Middle East—the perennial question of why nations falter demands urgent reflection.

Drawing on René Girard's mimetic theory, where imitation of desires breeds escalating conflicts, and Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson's Why Nations Fail, which critiques extractive institutions that hoard power and quash growth, this article explores how societies get ensnared in zero-sum power struggles. The path to failure is paved with polarization, scapegoating, and violence; the escape lies in channeling tension into creative, win-win paradigms.

Violence stands as the antithesis of creativity, emerging not merely from scarcity but from a failure to redirect mimetic rivalry—where humans imitate each other's desires, leading to zero-sum traps—into innovative outlets that generate abundance for all. Girard's framework reveals that human desire is rarely original; it is mimetic, forming a triangular dynamic of subject, model, and object. When desires converge on limited resources like power or territory, rivalry intensifies, often culminating in scapegoating: the ritualistic blaming and elimination of a victim to temporarily restore order. Yet, this only perpetuates the cycle.

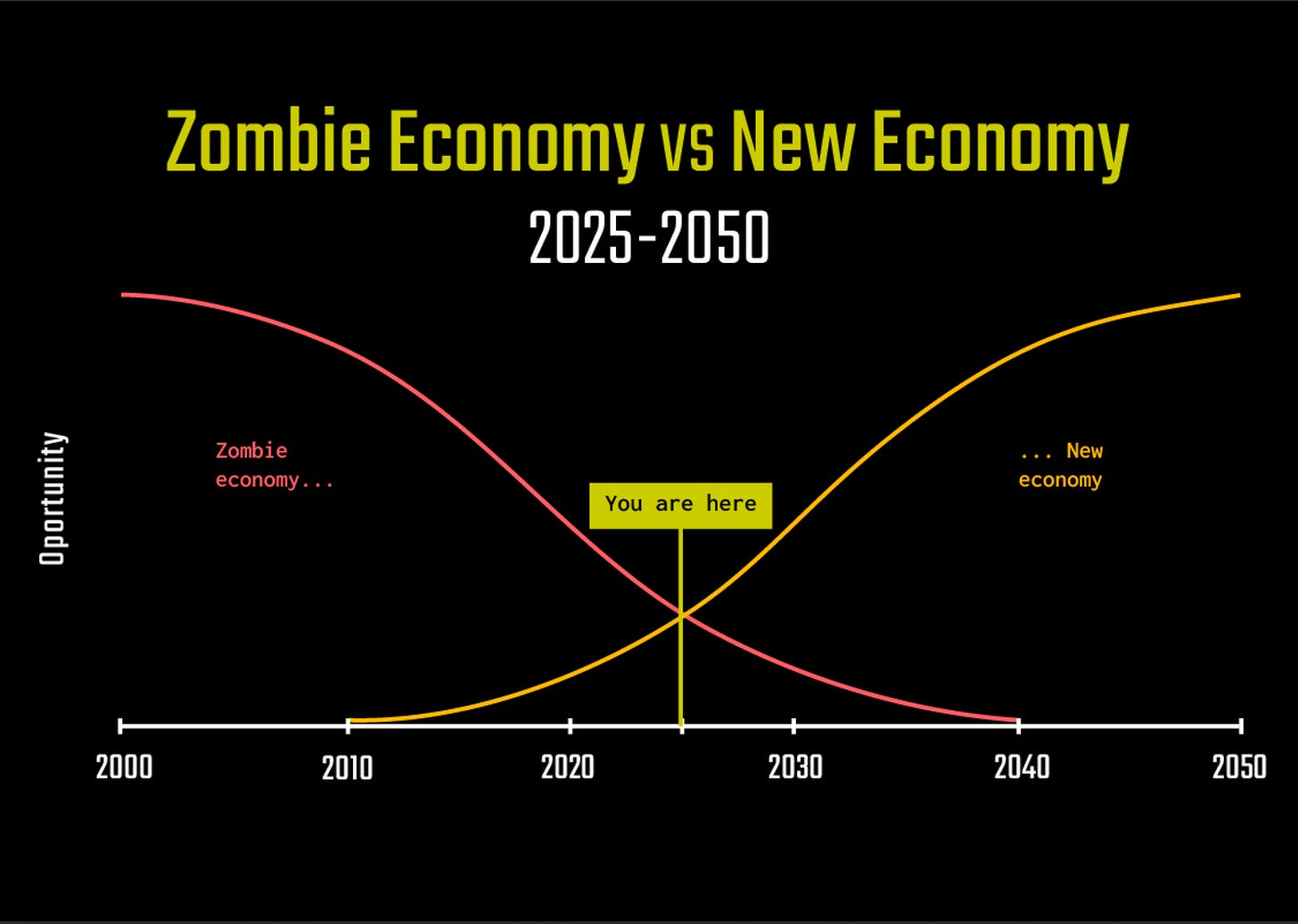

The antidote is "creative mimesis" or "loving mimesis," where imitation fosters innovation, shifting from destructive competition to collaborative progress.Moments of tension are inevitable in history. But what defines the future is how societies choose to channel that tension. When tension is transformed into a new technological revolution and into the creation of a different social paradigm, it becomes the seed of renewal.

When it is not, when tension is trapped inside the old system, it degenerates into a struggle for power—often fueled by mimetic rivalry, where desires are imitated and escalated into zero-sum conflicts, as René Girard describes.The longer societies procrastinate in making this leap toward a new paradigm, the more they become prisoners of polarization. That polarization manifests in two ways:

Externally, through geopolitical alignment and rivalry—nations forced to pick sides in an international conflict, mirroring each other's ambitions for dominance and resources.

Internally, through political polarization—societies torn apart by competing models of governance, where extractive institutions, as outlined by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson in Why Nations Fail, concentrate power among elites and stifle inclusive growth.

History provides us with clear examples.

In World War I, Europe failed to channel the energy of industrialization into a cooperative transformation, and instead collapsed into nationalist rivalries. Germany's imitation of Britain's imperial might escalated into catastrophe, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand serving as a scapegoat for deeper mimetic tensions between communism and capitalism. Empires like the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian clung to extractive systems, leading to their disintegration, while the United States redirected post-war energies into the New Deal and technological innovation, emerging as a superpower.

In the Cold War, rather than building a shared technological and social framework, the world became locked in two opposing blocs—progress existed, but under the shadow of permanent confrontation. The U.S. navigated internal scapegoating amid civil rights struggles and external proxy wars, but after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, it pivoted to the internet revolution and globalization, contrasting the USSR's extractive model that limited authoritarian growth. Latin America, including Colombia, became a theater for these proxy battles, with U.S. anti-communist strategies mirroring Soviet support for leftist insurgencies, birthing groups like the FARC (formed in 1964) and M-19 (arising from 1970 election fraud claims).

The Colombian Case, the inability to reinvent the economic and social model led the country to be trapped for decades in cycles of mafia wars, guerrilla insurgencies, paramilitary violence, and failed peace processes. Mimetic rivalries between guerrillas, cartels like Medellín and Cali, and the state resulted in scapegoats such as Pablo Escobar and Luis Carlos Galán, with power shifting factions without systemic change, perpetuating extractive poverty. Originating in the 1948 La Violencia civil war and amplified by Cold War dynamics, the conflict saw FARC and M-19 emulate global leftist models through kidnappings and extortion, countered by paramilitaries allied with landowners and drug lords. Narcotrafficking added layers, transforming rivalries into drug-fueled zero-sum contests. Post-Cold War U.S. aid via Plan Colombia (2000) focused on military efforts, weakening FARC but neglecting social and technological transformation. The 2016 FARC peace accord under President Juan Manuel Santos promised disarmament and inclusion but delivered a "false peace," redistributing power (FARC rebranded as Comunes) without addressing inequalities and not creating a new new economic game, leading to dissident rearmament and persistent paramilitary offshoots like the Black Eagles. Under President Gustavo Petro (elected 2022), the "total peace" policy negotiates with groups like ELN and allies with Venezuela's regime, aiming at social reforms but criticized for centralizing power and risking new mimetic rivalries without innovation. This stagnation was starkly illustrated by the June 7, 2025, assassination of Senator Miguel Uribe Turbay, a 39-year-old opposition leader and presidential hopeful, shot three times during a Bogotá rally; he succumbed to injuries on August 11. As a critic of Petro's policies advocating security and economic reforms, his death scapegoats a proponent of change, drawing international condemnation from figures like U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Argentine President Javier Milei, and the Vatican, who urged justice and probes into political violence.

The lesson is simple yet profound: clinging to the old system guarantees polarization, and polarization eventually leads to violence or war, as societies resort to scapegoating to vent mimetic tensions without addressing root causes.

The only way out of the cycle is to use moments of tension as catalysts to create something new—technologically, socially, and economically, through institutions that enable creative destruction and win-win innovation.

In today's emerging Cold War 2.0, from U.S.-China rivalries over AI, trade, and influence—marked by tariffs, supply chain disruptions, and potential proxies in the Global South—to precision strikes in the Middle East threatening regimes like Venezuela's, nations risk repeating these failures unless they embrace new games like the AI revolution. Without breaking free from extractive power structures, scapegoating persists, condemning societies to eternal conflict. Colombia's limited engagement in global tech surges, despite modest post-conflict digital gains, exposes it to these shifts, prolonging domestic battles.

But as Why Nations Fail shows, the path to prosperity lies in transforming rivalry into shared progress—forging a future beyond violence. To honor victims like Uribe Turbay, societies must invest in tech incubators, education, and collaborations, promoting creative mimesis to convert tension into abundance. Every society faces this choice: repeat the conflicts of the past, or transform tension into the architecture of the future.

Thanks for reading,

Guillermo Valencia A

Co-Founder of MacroWise

Thanks Guillermo for such a clear and profound analysis:

Transform the tensions in the Architecture of the Future!